Encampment Ban History and Legislation

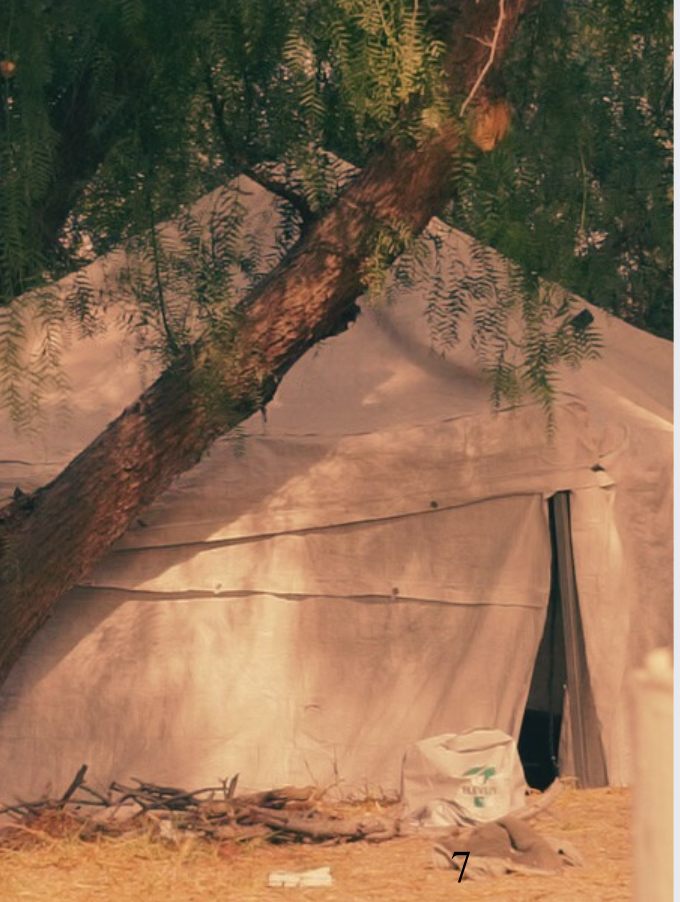

When people talk about homelessness, they often mean “Homelessness”—a state where one is living on the street. In reality, homelessness encompasses a spectrum of unstable living conditions that jeopardize health, safety, and personal welfare, including those sleeping in cars, cycling through temporary accommodations, fleeing domestic violence, or teetering on the brink of eviction. Since the 1980s, the emergence of modern homelessness, correlating with the Reagan administration’s policies of deinstitutionalization for the mentally ill and slashed housing program budgets, has transformed a crisis of tens of thousands into a staggering epidemic of over half a million people. Far from a singular issue, homelessness is a multifaceted social challenge, deeply intertwined with socioeconomics, human rights, ethics, politics, and culture. Yet, in a world with global issues deemed more “urgent” or “solvable” dominate the public agenda, tackling the systemic roots of homelessness has grown increasingly difficult, allowing its numbers to steadily rise. People often advocate for homelessness to be addressed at its “root,” but it is evident now that over the years, cities have made increasing efforts to hide poverty from the rest of society.

On June 28th 2024, the Supreme Court justices ruled in a 6-3 decision that it is not “cruel and unusual” punishment for city officials to ban those experiencing homelessness for sleeping in public areas. This act, allowing cities in the United States now to ban homeless encampments, surprised everyone and alarmed many, including Assistant Professor of Sociology Chris Herring from UCLA.

“Approximately 90% of unhoused individuals displaced by encampment bans end up back on the streets," said Herring. "These bans perpetuate poverty."

Moreover, unhoused individuals who do not evacuate encampments face arrest, leading to criminal records that hinder future opportunities for housing vouchers or employment, making it difficult to improve the quality of life.

While it is a commonplace for the Democratic perspective to defend a viewpoint similar to Herring’s, Governor Newsom of the blue state of California has actively supported this ban, issuing $1 billion in funding to clear encampments. Democratic swinging cities in California disagree with Newsom’s encouragement, stating that the ban is just “making the issue invisible,” exacerbating US homelessness rates 18% higher in 2024 since the past year, continuing with a clear upward trend. Conversely, Republican swinging cities tend to support the ban, claiming that this action is necessary for hygienic streets and will effectively force unhoused individuals into seeking resources such as non-profit organizations or government re-housing programs. However, the overcrowding of homeless shelters, coupled with unsanitary conditions and the cycle of individuals being repeatedly pushed back onto the streets, raises significant concerns about the well-being of unhoused individuals. This not only highlights a public health crisis but also underscores a moral issue in how society addresses homelessness.

But how did we reach the extent of this legislation and the increasing emphasis on enforcement rather than addressing systemic root causes? To grasp the underlying factors shaping the current approach to encampments, it is essential to examine the historical trajectory of legal rulings and their broader societal implications. The transition from Martin v. Boise to Pass v. Johnson represents a notable shift in addressing homelessness.

In 2018, the United States Court of Appeals passed the Martin v. Boise ruling, stating that cities cannot enforce anti-camping ordinances without sufficient facilities and resources for the homeless population. This ruling implied that those sitting in, sleeping in, or lying in public spaces have the right to do so if they do not have anywhere else to go. However, the Martin v Boise ruling did not mandate cities to establish new shelters for the homeless population nor obligate them to provide increased help. Moreover, cities and local governments could still impose reasonable time, place, and manner restrictions for the homeless population.

Despite the Martin v Boise ruling, the Supreme Court recently passed a subsequent ruling, the Pass v. Johnson, which effectively overturned the decision made in Martin v. Boise. The City of Grants Pass v. Johnson ruling gave cities the right to enforce laws and criminalize homeless individuals without violating the Eighth Amendment, which bans the government from giving ‘cruel and unusual punishment’ to the citizens. Amongst the various reasons behind this ruling, one controversial explanation stands out: it is constitutional for cities and local governments to remove and punish homeless populations because the punishments are not ‘cruel and unusual.’ The consequences may include short jail sentences and fines, which the Supreme Court decided are ‘reasonable’ consequences that do not infringe upon the Eighth Amendment. In the end, nonetheless, the ruling never clarified if it was constitutional for cities to give fines that homeless people could not physically pay for. Another prominent reason behind this ruling was that cities enforcing anti-camping ordinance laws were not purposely attacking a homeless person’s status, but rather their actions that impacted the larger community.

Numerous cities and local governments have demonstrated varying responses after the Martin v Boise and Pass v Johnson rulings. Long Beach, California, spent time refining and creating encampment programs and services in ‘focus areas,’ or areas already exposed to critical issues and disputes regarding homeless encampments and/or have received outreach services. In Long Beach’s strategy, the City’s Public Spaces Workgroup took an interdepartmental approach to address the focus areas’ homelessness problems, cooperating with the police department, Homeless Services Outreach, and other institutions such as the Emergency Communications Center. Similarly, in Oregon, after the City of Grants ruling this year, there was a revisit to HB3115, a bill allowing homeless people to remain on public property if no shelters are available, to make adjustments to the law. Hence, it abided by the new ruling and maintained established systems and policies regarding the homeless population. For instance, local officials in Oregon drafted revised restrictions and guidelines for the time, place, and manner of regulations for encampments on public property. After the Martin vs. Boise ruling in some cities, like Seattle and Spokane Valley, government officials modified their ordinance plans to allow for greater homeless encampments and transitional shelters set up in public spaces.

Regardless of how successfully or unsuccessfully different cities have responded to the most recent Pass v. Johnson ruling, there is no doubt that countless Supreme Court decisions are doing any good to the homeless crisis in the United States, especially in the West Coast. One cannot say whether or not these rulings are requirements for local governments or simply ‘incentivizing acts’ that provoke specific discriminatory measures against the homeless population. The federal passing of Grant Pass v Johnson has enabled various responses from local governments. With more than 100 US cities having already banned homeless encampments in 2024, predictions for future legislation foresee a continuation of the current pattern. The new constraints are pervasive, present in both cities and rural areas, and are not necessarily correlated with the political orientation of the locality. Cities have instituted bans in states such as New Hampshire, Oregon, Montana, Florida, and Texas. California, the US state with the largest homeless population, accounting for 27.89 percent of the national estimate according to World Population Review, has witnessed significant expansion of laws pertaining to homelessness.

Governor Newsom’s encouragement of encampment bans coupled with the Supreme Court’s ruling have led several California cities to recently tighten their policies towards homeless encampments. After reporting a 104 percent increase in homelessness in their 2024 Point-in-Time Count, San Joaquin County, bridging northern and central California, has taken advantage of the recent federal ruling to push an ordinance banning car sleeping and forcing unhoused individuals to move a minimum of 300 feet per hour. This ordinance aims to create uncomfortable conditions for the homeless population in hopes of encouraging more appropriate living conditions, but research shows it will merely create temporary relief from encampments and a cyclical process of unsettling the unhoused without permanent solutions. The City of San Diego passed an Unsafe Camping Ordinance to begin on July 31, 2023 prohibiting encampments on public property and codifying how, when and where the City may abate or conduct enforcement related to violations of the regulations. The City outlines a scaled approach, targeting homeless encampments near schools and parks most significantly impacted by encampments. Regardless of shelter availability, law enforcement must address violations under specific conditions including within two blocks of K-12 schools, within two blocks of a shelter, in city parks, and in any open space, waterway, or banks of a waterway.

However, despite trends illustrated in San Diego and San Joaquin County, California’s most impacted city, Los Angeles refrains from banning encampments. Instead, they plan to continue their pricy strategy of providing temporary housing in the form of hotel rooms until lasting accommodations become available. Other California cities threaten further restrictions such as Santa Monica which presently considers a ban on sleeping bags.

Disincentivizing encampments necessitates suitable resources and housing to sustain and support the homeless population – criteria many cities aren’t equipped to meet. Data from The Public Policy Institute of California, reflects that California’s shelters have the capacity to house 40% of the homeless population, leaving the excess 60% without shelter or support from their local governments. Therefore, a statewide ban of encampments would criminalize homelessness and displace at least 100,000 individuals.

California exemplifies a national trend of encampment bans despite a lack of affordable housing and available necessities for the unhoused. Local governments across the United States are now instating new laws and ordinances against their homeless populations. By neglecting to confront the root of homelessness and, instead, further drown those affected with the burdens of arrests, fines, and constant displacement, the spreading of encampment bans may prove detrimental to mending the homeless crisis. With officials veiling the broader plight of homelessness through temporary movement of homeless individuals and further restrictions, one can safely expect an increase in the unhoused population as necessary support is further delayed by the federal government’s inaction and inability to protect its unhoused citizens.